By Jews and Judaism in the Modern World Students

April 2017

Introduction

On the ground floor of Long Hall at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary sits the Kelso Museum of Near Eastern Archaeology. Despite its small size, the museum contains a large variety of artifacts from the Near East, including a 300-year-old Yemenite Torah scroll. While it is unclear exactly how the museum acquired the scroll, the curators consider it an essential part of their exhibit, as it provides guests with a look into the development of writing. The scroll is also non-kosher or pasul Torah and no longer fit for ritual use.

History of the Scroll

There is no clear record of how the Kelso Museum came to obtain the Torah scroll that they currently have on display, as they found it in their archives in 2000 in the process of expanding their exhibition. It is believed that a faculty member of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary had brought the scroll to the school in the 1950s. When the museum contacted the faculty member to see if this was true, he said he did not know anything about it.

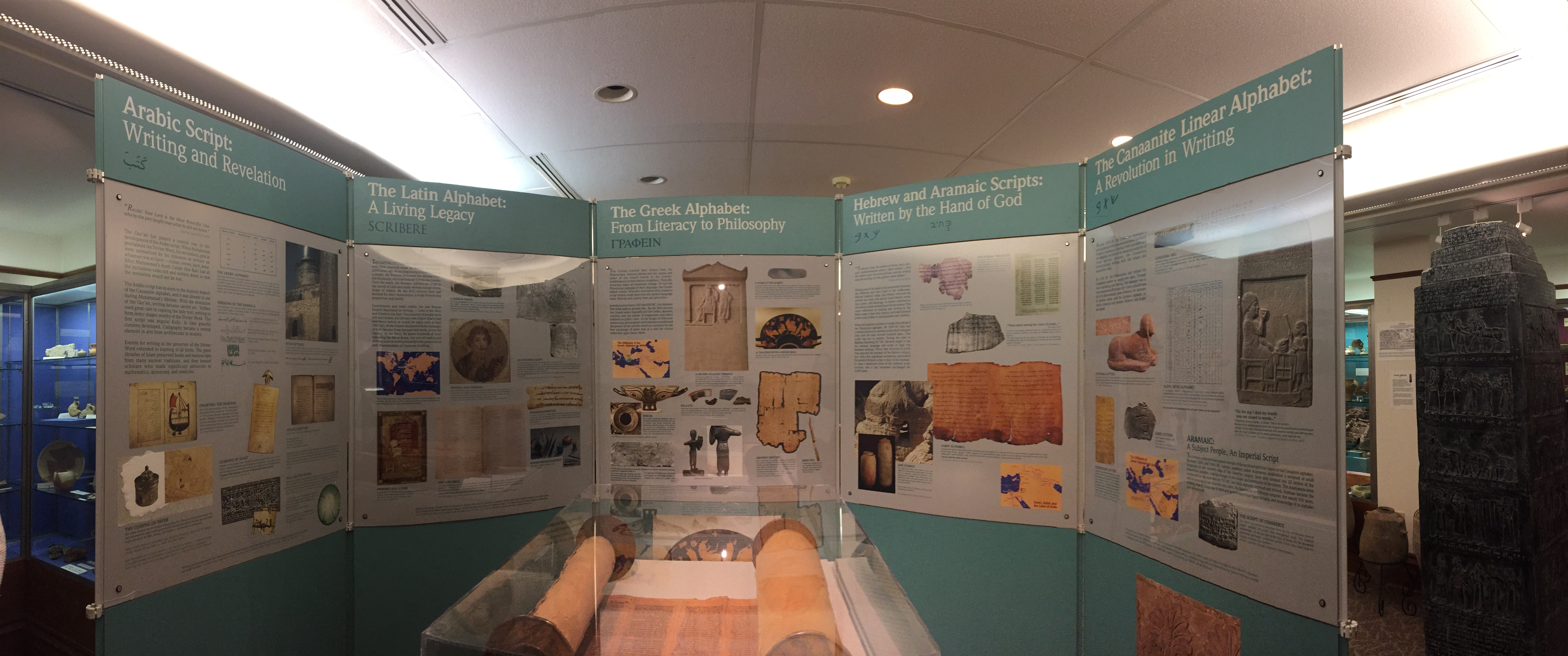

The scroll is a part of an exhibit entitled “Words Made Visible: The Origins of Writing and the Early History of the Alphabet.” It is placed in the center of a display chronicling the development of the alphabet in different traditions, including Arabic, Latin, Greek, Aramaic and the Canaanite Linear Alphabet. The scroll is displayed in a stand-alone glass case that is temperature controlled.

There can be controversy associated with displaying an open Torah scroll, as it is a holy living document. On the occasion that it is no longer usable in the traditional setting, it is customary for it to be buried or put into storage in a Geniza. Before displaying the scroll, Karen Bowden Cooper, the resource curator consultant for PTS, consulted experts in order to decide if it was respectful to display it.

The Torah was examined by a scribe from New York, according to Cooper. The scribe identified it as Yemenite and estimated that it was about 35-400 years old. The Sefer Torah is believed to be Yemenite because of its arrangement of the Song of the Sea. This is the song that Moses and the Israelites sang after the parting of the sea and is recited during the Shacharit prayer service. According to the scribe who examined it, this is not a kosher scroll. Although it is on deerskin, a kosher parchment, the Torah did not benefit from a tanning prcess that is necessary to create a kosher Tora. How the scroll got to America and the museum remains a question to this day.

Cooper also noted the breaks in the Torah, which she believes suggest that the scroll was used for the sole purpose of studying rather than ritual practice. Additionally, close examination of special letters and extraordinary points in the writing suggest that there were multiple hands, as many as three, working to complete the Torah.

According to Jennifer Hipple, Associate Curator of the Kelso Museum, the scroll is often a favorite of those who come to see their exhibit, and visitors are surprised to find something so unique in such a small museum. She also says that many of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s beginning Hebrew students enjoy coming to the museum and trying to see what they can read from the Torah.

Though it is not in ritual use, this Torah scroll benefits the larger Pittsburgh community in a variety of ways. Both Cooper and Hipple believe that it greatly enhances their exhibit, offering guests a look into the history of writing and the development of monotheistic religion.

History of the Museum

The Kelso Museum of Near Eastern Archaeology of the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary houses a significant collection of artifacts from ancient Israel and Jordan, some dating back as far as the Early Bronze Age.

The museum’s commitment to archaeology can be traced back to 1908 when Rev. M.G. Kyle became the first lecturer in biblical archaeology at a Protestant seminary. The Seminary’s first field work survey of the Dead Sea Plain and excavations of Tel Beit Mirsim was led by Kyle and W.F. Albright in 1924. Kyle’s archaeological work for the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary was continued by James L. Kelso, for who the museum was named, from 1930-1963, Paul Lapp from 1968-1970, and then Nancy Lapp from 1970-1997. The current professor of archaeology at PTS is Ron Tappy.

The museum itself consists of a work shop and two rooms that include highlights of their collection of 6,000 registered artifacts. The collections come from four different sites. The first, Bab Edh Dhra, is the site of an Early Bronze Age city located on the eastern side of the Dead Sea. The second, Tel Beit Mirsim, is a series of cities dating back to the Bronze and Iron Ages, located in the southwestern foothills of Canaan. The third site is Bethel, situated on the border of ancient Israel and Judah, from which artifacts dating from Chalcolithic through Roman times have been discovered. The final archaeological site represented in the museum is Tulul El Alayiq, which was a palace complex near Jericho that dates to Hellenistic times, and was then was later renovated by Herod the Great, a Roman client king of Judea.

Not only does the museum have a large collection of artifacts, but it also holds primary records documenting their excavations. This includes diaries, day books, drawings, photographs, maps, correspondence and account books. According to Jennifer Hipple, associate curator, their 16 mm movie footage of the excavation at Tell Beit Mirsim in 1930 is possibly the first footage of an excavation in the Near East and possibly even in the world.

The museum follows different threads of history in its five exhibits. The first is the people of the Dead Sea Plain, and showcases artifacts dating between 3300-2000 BCE. It looks specifically at towns and and tombs revealed through excavations at Bab Edh Dhra. The next segment of the exhibit follows the foothills of Canaan from 2000-1000 BCE, displaying artifacts and graphics that look at daily life in the areas that are now Israel, West Bank, and Jordan. It shows the evolving patterns of the society in terms of settlement, technology, craft and social organization. The third exhibit is called Tell er Rumeith: An Outpost on the Incense Road. It shows artifacts from a site in northern Jordan that date back to between 930 and 730 BCE.

The fourth exhibit is A Photogenic Memory: Ninety Years of Archaeological Fieldwork at PTS. In this exhibit, the museum showcases the Seminary’s history of archeological exploration. With it, the museum hopes to show changes in archaeological technique and culture.

The exhibit featuring the Torah Scroll is in a section of the museum called Words Made Visible: The Origins of Writing and the Early History of the Alphabet. It traces the origins of writing and the alphabet through inscribed artifacts and large-scale replicas. It looks at the practice of writing in Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Canaan-Israel and how it developed from cuneiform and hieroglyphs.

History of Jews in Yemen

A scribe determined that the Torah scroll on display at the Kelso museum is most likely of Yemenite origin. What do we know about the community that produced this scroll? How did Jews end up in Yemen, and where are their descendents today?

Unfortunately, the community’s history is a tumultuous one, and most of the Jews in Yemen experieced persecution that forced them to emigrate elsewhere. Most Jews of Yemenite descent live in Israel today, although somewhere between 200 and 2,000 continue to live in Yemen.

Jews have had a presence in southwest Arabia (today Yemen) for at least 1,500 years, probably having descended from the people of ancient Palestine. There are a number of legends surrounding their origin; one claims that 75,000 Jews traveled to Yemen after the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE, and another supposes that they arrived after the Queen of Sheba visited King Solomon’s court. The country of Yemen, however, makes no appearance in the Talmud (a collection of writings central to Rabbinic Judaism), leading scholars to believe the Jews first arrived in the early centuries of the Common Era. Some lived in large cities such as the capital city of Sana’a, but most settled in rural, predominantly Jewish villages.

The Jews of Yemen had their own distinct Jewish practices, community organizations, and methods of artistic expression. Most were skilled craftspeople, and since the Muslims looked down on such manual labor, the Jews were able to dominate the market of handmade goods. While they spoke Arabic in their daily lives, men diligently studied the Hebrew Bible and many were able to recite entire books from memory.

The quality of life for the Jews in Yemen largely depended on the ruler of the time. Yemenite leader Yusuf Dhu Nuwas actually converted to Judaism sometime between 518–525. This Jewish leadership was short-lived, however, and Ethiopia soon invaded Yemen and killed Dhu Nuwas. From this point on, Yemen was generally ruled by Muslims who categorized Jews as dhimmi under their law. Dhimmi groups could practice their own religion, but did not have political or legal rights and needed to pay special taxes. Jews lived there without experiencing persecution until the 12th century.

In 1165, Muslim ruler Abd-al-Nabi ibn Mahdi ordered that Jews must convert to Islam or face execution, and in the centuries that followed Jews faced persecution by their leaders. Al-Mutawakkil Isma’il, the imam of Yemen from 1644 to 1676, again ordered Jewish conversion to Islam, and their refusal prompted his successor al-Mahdi to destroy synagogues, prohibit public prayer, and later ban Jews from the capital of Sana’a. In the 19th century, Zionist ideas became popular in Yemenite Jewish communities, and some began arranging for groups to emigrate starting in 1882. The creation of Israel sparked violence in Yemen, including a 1947 riot in the city of Aden in which 82 Jews were killed. This response further persuaded more Jews to leave the country.

As the status of the Jews in Yemen went sharply downhill, the Israeli government decided to intervene. Between June 1949 and September 1950, the government facilitated the airlift of 49,000 Jews from Yemen (as well as some from Eritrea, Djibouti, and Saudi Arabia) to the new State of Israel in a secret operation called Operation Magic Carpet (officially known as Operation On Wings of Eagles).

Today, the majority of Jews of Yemenite descent live in Israel, with over 165,000 Israeli Jews claiming Yemenite roots. While they are integrated Hebrew-speaking Israelis, they also retain cultural distinctions, such as the use of specific liturgical Yemenite Hebrew pronunciation in their synagogues and distinct religious rituals.

Kosher Torah Scrolls and Museum Display

The Hebrew word פסול (pasul) means “defective” or “disqualified.” The Kelso Museum Torah scroll is a pasul scroll, meaning that it is unfit for synagogue ritual. What exactly makes it a pasul scroll, and why is it okay to display such a scroll in a museum according to Jewish law?

Torah scrolls are created with the intention to be kosher. While the word ”kosher” is more commonly associated with food, this Hebrew word simply means “fit” or “proper” and can refer to a non-food item that is appropriate for sacred use. In order for a Torah scroll to be deemed kosher, it must be constructed from the hide of a kosher animal that has been properly tanned with the intention to be used in a Torah scroll. A sofer, a Jewish scribe, must carefully transcribe each character by hand with a quill pen and be sure to make no mistakes. Any mishap in the process could result in the scroll being deemed pasul.

Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, commonly known as Maimonides or Rambam, was an important 12th century Sephardic Jewish philosopher who designated twenty factors that would make a scroll pasul. These include making the scroll with the hide of an unkosher animal, with hide that is untanned, or with hide that was not tanned with the sole intention of being used to produce a Torah scroll. A scroll is also pasul if a single letter is missing or damaged to the point of illegibility, or if there is a tear in the parchment. However, this is not necessarily the point of no return. If the mistake can be fixed, such as with a marred character, the Torah can be deemed kosher again if the mistake is promptly fixed by a qualified sofer.

If a Torah scroll is damagedbeyond repair, such as if it is too old and fragile to fix or has been partially burnt in a fire, it is common practice to bury the scroll or put it in a storage area called a geniza instead of destroying it. Burying is considered more respectful because the scroll still contains the divine name regardless of its state of repair.

Most scholars of Jewish law agree that museums may display Torah scrolls for the purpose of education, since Maimonides endorsed using pasul scrolls for educational purposes. This is not limited to pasul Torah scrolls: according to many sources, even kosher scrolls can be on display at a museum if they are situated in a quiet environment that treats them with respect. When storing kosher Torah scrolls, synagogues will keep the scrolls rolled in an ornate case typically made of fabric, wood, or metal in order to prolong the life of the scroll as well as to respect its sacred nature. However, scrolls in museums are often open in order for the public to view the text. While such an open display is not inherently unkosher, exposure to light will slowly degrade the text, making it preferable to display primarily pasul scrolls in museums.

Due to extensive damage and age, the Kelso Museum Torah will never be a kosher scroll. However, even if it cannot be used for its original religious intentions, it serves as a valuable resource to educate the public about rare ancient texts.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Karen Bowden Cooper and Jennifer Hipple for taking the time to provide the known history of the Kelso Museum Torah.

Further Reading

Abelson, Kassel. “Display of a Pasul Torah in a Museum Case.” The Committee on Jewish Laws and Standards. June 7 1997, https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19912000/abelson_pasul.pdf.

Toby Tabachnick, “A rare find exhibits rarer finds at Presbyterian Seminary,” Jewish Chronicle, October 7, 2015.

Barfi, Barak, and Yael Katzir. “Jews in Yemen.” Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture, edited by M. Avrum Ehrlich, vol. 2: Countries, Regions, and Communities: Part One, ABC-CLIO, 2009, 793-799.

Kelso Museum. “Current Exhibits at the Kelso Museum of Near Eastern Archaeology.” Accessed March 12, 2017. http://www.pts.edu/Current_Exhibits

Jaffee, Martin S. “Torah.” Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Lindsay Jones, 2nd ed., vol. 13, Macmillan Reference USA, 2005, 9230-9241.

Lewis, Herbert S. “Jews of Yemen.” Encyclopedia of World Cultures, vol. 9: Africa and the Middle East, Macmillan Reference USA, 1996, 149-151.

Rothkoff, Aaron, and Louis Isaac Rabinowitz. “Sefer Torah.” Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 18, Macmillan Reference USA, 2007, 241-243.

How to Cite

MLA: Jews and Judaism in the Modern World Students. “Kelso Museum Torah.” ReligYinz: Mapping Religious Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh, April 2017, https://religyinz.pitt.edu/kelso-museum-torah/.

APA: Jews and Judaism in the Modern World Students. (2017 April). Kelso Museum Torah. ReligYinz: Mapping Religious Pittsburgh. https://religyinz.pitt.edu/kelso-museum-torah/.

Chicago: Jews and Judaism in the Modern World Students. “Kelso Museum Torah.” ReligYinz: Mapping Religious Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh, April 2017. https://religyinz.pitt.edu/kelso-museum-torah/.